By Jarrod Olson, Director of Health Analytics

Is Invermectin safer than the COVID vaccines? Will the vaccines make me infertile? I hear that the COVID-19 vaccines change your DNA, is that true? News reporters, doctors, nurses, and the scientific community have been correcting this sort of inaccurate information since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. More than two years later, musical artists are leaving Spotify because of podcasts that discuss these same topics. Harmful, inaccurate information is everywhere, and it’s not going away.

It spreads through social media bubbles. It spreads through word of mouth. It spreads quickly like the COVID-19 virus itself. The effects are similarly devastating. At the time of publishing this article, the U.S. is inching toward 1 million COVID-19 deaths – the highest national number of COVID-19 deaths in the world. The WHO and U.S. officials say that misinformation is a “serious health threat” and its spread is preventing people from getting the vaccine. The U.S. is one of the most connected, most wired, and most misinformed nations in the world. However, this is not a uniquely domestic problem. Inaccurate information around the globe spreads quickly and is more poorly policed by organizations like Facebook, which has focused on English-language misinformation. If we are to be successful in combatting this pandemic or any other future public health emergency, we will have to become successful at combatting misinformation. This article is the first in a series that we will present in the coming weeks on how to combat misinformation and all forms of inaccurate information.

The Birth of Information Disorder

Before you can successfully tackle a problem, however, you must understand it. Like so many things in the past, today’s misinformation environment was born of simple advances in technology that allowed classic patterns of inaccurate information dissemination to reach new heights.

The internet, particularly social media, allowed us to connect in ways we have never known before. Mobile phones and mobile apps made it that much easier and faster. Algorithms were developed to help organize content and streamline the user experience. With so much information out there, algorithms helped recognize the user’s preferences and served up content of interest.

Like all new technologies, however, there are challenges. Algorithms designed to pull in users and to build community created biased echo chambers that reinforced and entrenched user views and provided an opportune landscape for the spread of inaccurate information. Large audiences interested in the same topics, watching and reading the same things – well, that is how television advertising began. A captive audience is appealing to companies selling products, organizations selling philosophical ideas, politicians seeking votes, and individuals wanting attention or seeking to harm others. Individuals built “trusted networks” online without fact checking or accountability for spreading inaccurate information, leaving even well-intentioned people in a position of spreading potentially harmful information more widely than their in-person network. New technology did not create the problem now known as Information Disorder Syndrome, but it vastly increased its negative impacts.

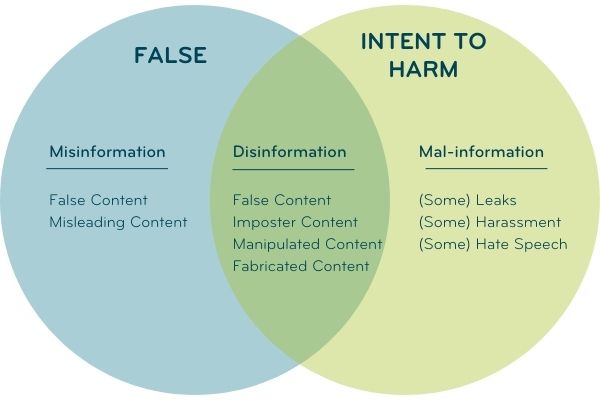

Source: firstdraftnews.org

According to the Journal of the National Medical Association, Information Disorder Syndrome is the “sharing or developing of false information with or without intent of harming, and they are categorized as misinformation, disinformation, and mal-information.” Each category relates to one of two key characteristics: “Falseness” (i.e., how made up is this information), and “Intent to Harm” (i.e., was this information shared with intent to harm?). Misinformation is false information shared without an intent to harm. Disinformation is false or misleading information spread with the intent to harm. To these medical definitions, which may have treatment modalities, firsdraftnews.org adds the concept of mal-information, which is truthful information spread without important context with the intent to harm.

Why is Information Disorder and monitoring content a dilemma? For one, it is a technical challenge. Small nuances in statements change potentially true information into false information and hundreds of millions of users and billions of posts per day. Additionally, monitoring misinformation walks a fine line of monitoring speech. Free speech is a cornerstone of democracy. Should companies or the government monitor and remove harmful inaccurate information? When does skeptical speech transform into speech spreading misinformation? Skepticism is a cornerstone of the scientific process and allows individuals to consider different perspectives and avoid groupthink.

From our perspective, however, public health is a unique issue. Public health exists to save lives. Information Disorder can kill people – large numbers of people. The COVID-19 pandemic is proof of that. Many unnecessary deaths are attributable to the ill-effects of Information Disorder. Hospitals are overwhelmed and healthcare workers are weary and frayed by the ongoing battle with this virus. A thoughtful, transparent, and systematic approach to monitoring and response for Information Disorder outbreaks is a critical tool for public health responders.

From masks to vaccines to other therapies, Information Disorder has taken a toll on this country as it relates to public health. It’s infecting communities. It’s infecting school districts, offices, and city councils, and it is making the COVID-19 crisis worse. People are dying unnecessarily. People are hospitalized unnecessarily. People are infecting their own families, their friends, and their neighbors with both inaccurate information about COVID-19, and the COVID-19 virus itself. It raises the question when does misinformation about a deadly virus or vaccines create a clear and present danger to others – to society as a whole?

As part of our work with the COVID-19 Task Force, we have conducted research to understand people’s behaviors and attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccines. We found that people who strongly trust the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are 48.5 times more likely to get their child vaccinated than those who strongly distrust CDC. Science shows that the vaccines reduce the likelihood of severe illness (hospitalization) and death. Would this pandemic have lasted as long and killed as many people if Information Disorder had not been such a big part of the issue both domestically and abroad? We can’t answer that with certainly, but we can make it part of planning for future pandemics.

Responding to Information Disorder Outbreaks

While many gray areas need to be worked out in the bigger misinformation picture, some steps can be taken to prevent another pandemic like this one. Tracking and treating misinformation like a virus is one way of doing this. Responding to critical Information Disorder “outbreaks” early with counter-messaging campaigns could avoid confusion, encourage trust, and save lives. While remaining silent on lower profile outbreaks avoids unnecessarily raising the profile of a misinformation issue.

In fact, understanding when and how to intervene is critical to prioritize resources efficiently and effectively. With a high-volume of content and long lead-times for public health messaging, detecting viable threads of misinformation, disinformation, and mal-information earlier increases the likelihood of an effective counter-messaging campaign.

Treating Information Disorder like a disease and outbreaks like infodemics are evolving concepts, but the idea closely resembles modern epidemiology’s framework for surveilling, studying, and responding to public health crises. John Snow pioneered modern epidemiology by mapping deaths from cholera and investigating the spatial correlation with key water supplies. He identified contamination of those water supplies and inferred that they were the cause of the outbreaks. He removed the source of contaminated water and reduced the disease burden.

Similarly, we know how to characterize the disease of Information Disorder, and we have a general sense of where it comes from – social media, media platforms, public figures, neighbors, and others. The study of infodemiology is needed to better understand how to characterize and respond to misinformation outbreaks. It is critical to modern-day public health.

In coming articles, we will present methods for developing an infodemiology framework to combat the virus of misinformation.